This blog is part of Joe Hinsberger’s ENVS491 course. As part of his assignment and to prepare for the interview, he read a past interview and several blog posts that Tony wrote while serving as construction manager

As a civil engineering student, I’ve always been curious about the real-world challenges behind what we study in class. So when I had the chance to speak with the RORG’s former project engineer Tony Heath, I jumped at it. When he joined the project team led by our director Eliana Brown, he was in grad school and already had work experience, including a professional engineering license. Although five years have passed, his insights and memories remain as fresh as ever. Our conversation covered technical reflections to personal philosophies, offering a behind-the-scenes glimpse into his role designing and building a living piece of green stormwater infrastructure on a college campus.

“If I had to do it again…”

We started with a deceptively simple question: If you could do the project over again, what’s something you’d do differently?

“The biggest difference now is just having more experience,” he said. “I think I would’ve done a much better job anticipating challenges.”

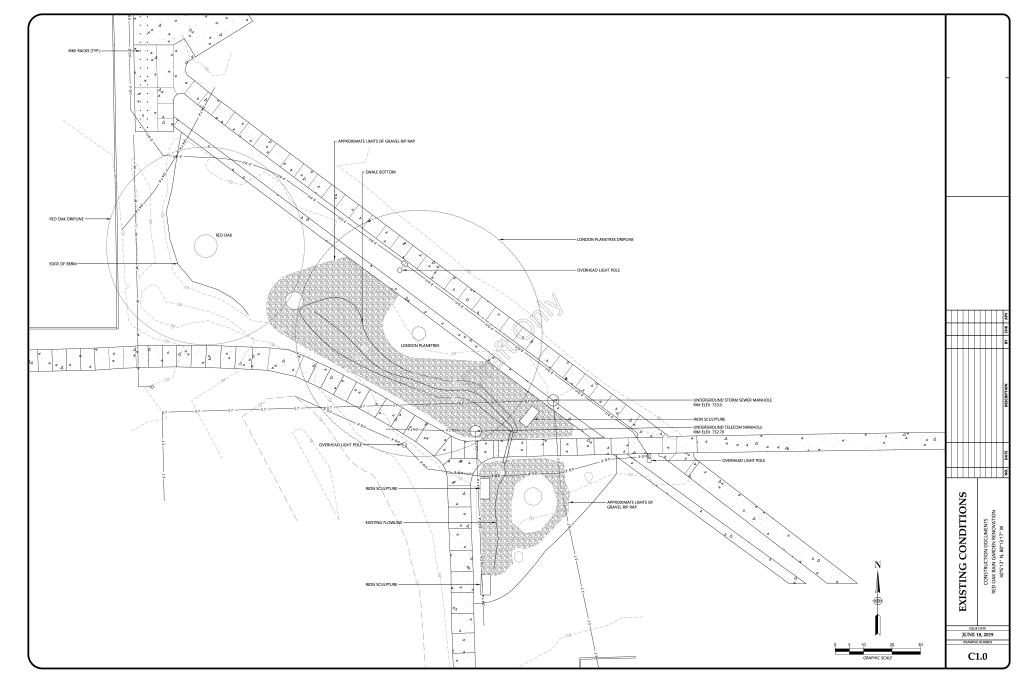

Design-wise, he reflected on the grading between the sycamore and red oak trees. “I would have simplified the grading there and tried to shallow it up. I think I tried to get too much like storage volume in the garden itself, and it ended up being kind of an unusual shape. I think we over-dug it a little bit. I would have done less disturbance to the ground and trusted the plants to do more of the work in infiltrating and capturing some of that stormwater.”

He also acknowledged how early-career engineers often cling tightly to the standards and methods they’ve been taught. “When you don’t know, you tend to rely on standards a lot. You think, ‘This is the standard way to do it; this is what the book says.’ But as you become more familiar with processes and start seeing what works and what doesn’t, it becomes easier to say, ‘Okay, this is what the book says, but this is what makes the most sense here.’”

Experience vs. Intention: Working with contractors

Tony reflected on what it was like to be a young engineer collaborating with experienced contractors, and how it took open communication to balance ecological goals with other project concerns.

“Especially when you’re a recent graduate, standing there in your neatly pressed polo and spotless hard hat,” he said, smiling. That image often stands in stark contrast to the seasoned contractors who had been doing this kind of work for decades. “There’s definitely a push and pull,” he added. “They bring a wealth of practical knowledge and do know a lot more than you, but at the same time, you know that certain design choices were made intentionally. Over time, you start to build confidence in your decisions.”

Still, he found it useful to stay open-minded. “When you’re just starting out, you nod and say, ‘Yeah, that’s what I was thinking too,’ and learn from how others approach the work,” he added with a laugh, “because for the most part, they are right, given their experience”.

At the Red Oak Rain Garden, the setting allowed for more collaboration. Instead of a large contracting team, the work was done in partnership with a small facilities crew. “This was a really valuable learning experience,” Tony said. “We were able to talk things through. Like, ‘Here’s what we’re trying to do,’ and they’d say, ‘That might not work.’ So there was a lot more back-and-forth and discussion. It was very beneficial for me to get the opportunity to have a close working relationship with the people that were building it.”

Photo by Kate Gardiner.

What’s underground matters

One memorable construction moment came when the team unexpectedly hit a layer of dense clay while digging in the rain garden’s prairie cell. Soil conditions can vary widely, even within the same site. Understanding those conditions is crucial to ensuring a rain garden works properly. “That’s a huge part of it,” Tony explained. “It’s important to do soil borings and infiltration tests before installing a rain garden.”

Because RORG had already been a functional rain garden, the team only conducted soil borings west of the red oak, beyond the original 2006 footprint of the garden. “If you’re working in a city or on a university campus that’s been built up and heavily modified over time, you never know what you’ll find.” In our case, we uncovered bricks—yes, actual bricks—buried several feet below the surface of the prairie cell.

A daily concern: soil compaction

The potential for soil compaction was a constant concern during construction and Eliana ensured that we were mindful of avoiding it. “Construction traffic compacts the soil, collapsing its pores and reducing its ability to absorb and store stormwater.”

But it wasn’t just about stormwater capacity and infiltration. “We had these two 100-year-old trees, which are focal points of the garden, and construction traffic around trees. You may not see it right away, but within a few years, compaction could kill the tree just from enough sustained damage to its roots.” To minimize this damage, the RORG Team worked with Facilities & Services to follow best practices from the National Green Infrastructure Certification Program and fenced off critical root zones around the tree trunks.

When the plans change

During construction, the team realized they needed to shift the location of a swale to better avoid tree roots. This raised an important question: how are mid-project changes like this documented?

“If it’s a major change, you’d typically issue an addendum or a revision,” Tony explained. “That means updating the construction drawings and sending out the revised sheets. For smaller changes, they’re often made in the field and then noted later on a record drawing, or ‘as-built.’”

Tony pointed out that while as-builts, which show what was actually built, are technically required, they’re often overlooked. This can cause serious issues down the line. “You might be working off an old set of plans that show a sewer or water main in one spot,” he said, “but when you dig, you find it’s actually 12 feet away.” So, he updated the drawing set, which is now with F&S Documents.

Navigating campus-wide interest

Tony shared that one of the most rewarding aspects of the project was the widespread interest it generated across campus, from departments like linguistics to art.

“During construction, the people who stopped by to learn more or just chat about the project. That was always kind of the highlight of the day,” he said. “Everyone was really curious and engaged.”

Behind the scenes, coordinating that broad interest came with some challenges. “The more complex part wasn’t on-site, but in managing input from the many university groups who wanted to be part of the process,” Tony noted.

He emphasized how valuable the Eliana’s role was in bringing those voices together. “That kind of coordination can be tricky, but she handled it deftly. And really, it speaks to the collaborative spirit that’s so common in university settings.”

Why he does it

We wrapped up with a big-picture question: What motivates someone to stay committed to this kind of work?

After a moment of reflection, Tony shared, “I would say that my passion comes from a sense of stewardship. I think this work is important, and I want to contribute to something that benefits our community and the places we live, something that leaves the world better than we found it.”

He added that his motivation also stems from a blend of personal and professional interests. “I love natural landscapes. And the engineering, numbers-driven side of my brain appreciates how efficient it can be. We can hit measurable environmental goals while also creating places that are beautiful and welcoming, where someone might just sit on a bench and enjoy the space.”

RORG is more than a garden

Talking with Tony reminded me that the Red Oak Rain Garden isn’t just a garden; it’s a story. A story of hard work, unexpected discoveries, delicate negotiations, and deep care. It’s a project that required imagination, collaboration, and a willingness to get your hands dirty, literally.

It’s easy to see a finished project and forget all the steps it took to get there. But every curve of the swale, every choice in soil, every plant placement came from conversations, adjustments, and real people doing thoughtful work.

As Tony put it, “You never know what you’re going to find,” whether that’s underground, in your collaborators, or within yourself.

Photo by Kate Gardiner.

Joe Hinsberger just completed his sophomore year studying Civil and Environmental Engineering at Illinois. He is passionate about expanding access and connection with nature, especially in urban environments. He is the first RORG Student Team member to receive course credit through ENVS 491: Sustainability Experience. In his free time, he enjoys working out and hiking.