For Illuminating Art in Nature, the Red Oak Rain Garden is honored to partner with Professor Lindsey Stirek and students in ARTJ299 to explore the connection between Japanese film studio Studio Ghibli and ecology.

Studio Ghibli has become an internationally renowned animation studio known for its immersive storytelling, fantastic art, and compelling messages. Their stories can be fantastical, mundane, and everything in between, but their messages are all drawn from the same source: a profound appreciation for what it means to live as a human on this earth and a deep respect for the natural world. To this end, Ghibli films evoke in their viewers a sense of connection—to people, to nature, and to a sense of purpose. But the intention of the directors of these films was never for our connection to be confined to a screen. Their films call out for us to go out and find our purpose, sit and listen to the sounds of the earth, and live in a way that protects the people and places we love.

For this exhibition, I asked the students to consider the many ways Studio Ghibli conveys environmentalist themes and to find ways of their own to draw people into connection with nature through these films. On this blog page you will find their reflections and original artworks covering nearly all of the films in the Ghibli collection. Their reflections demonstrate a wide range of understandings of nature, but all these understandings come back to the sometimes beautiful, sometimes devastating, but always inescapable circularity of our relationship with the environment, highlighting the critical importance of cultivating a relationship of mutual respect and reciprocity.

I hope you enjoy the blog and feel inspired to come out to the Red Oak Rain Garden and experience nature with us!

– Professor Lindsey Stirek

My Neighbor Totoro

by Joaquin Ancheta

The Studio Ghibli film, My Neighbor Totoro, explores the familial bonds people can experience not only by blood, but by a community, and more importantly with nature. The titular character of Totoro, is a mythical forest spirit, and friend to the protagonists of the story who are young children, recently moved from the city to the countryside. The association between childhood innocence and curiosity, and the wondrous things nature provides such as beautiful scenery and interesting wildlife is portrayed through a whimsical and dynamic way in this film. Just like with a tight knit community, when the two main siblings are in dire need for help, their neighbors they made bonds with came to their rescue, as did Totoro and the other forest spirits, who help the siblings reach the destination they needed to go in the climax of the film. It goes without saying that nature can not only be beautiful, but is also an important part of growing up and learning what it means to be neighbors.

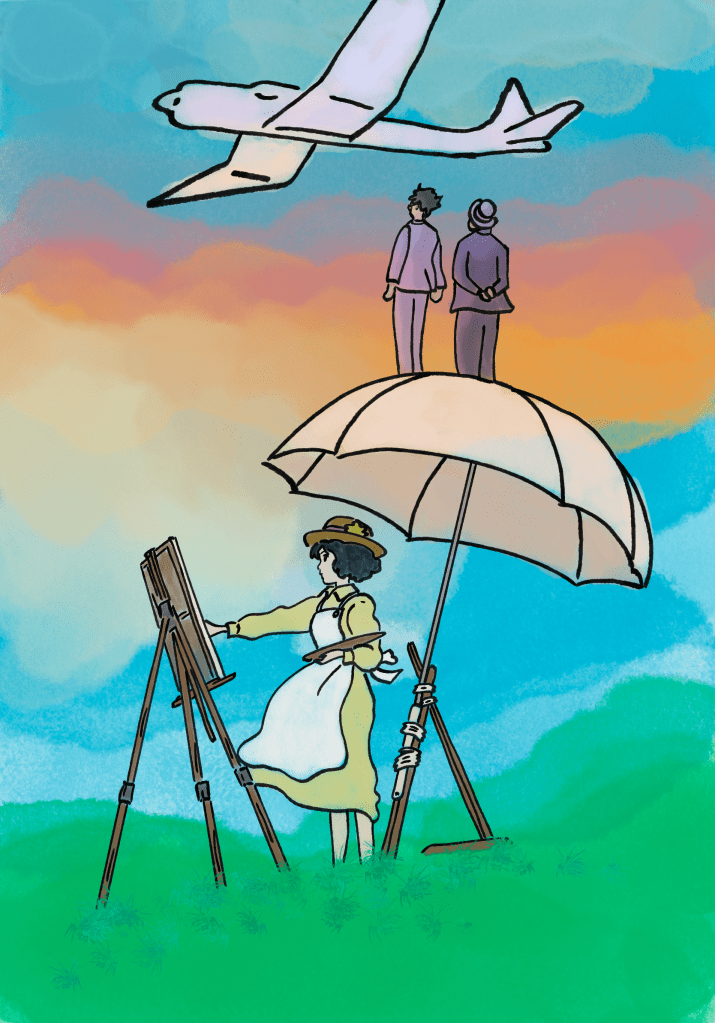

The Wind Rises

by Zee Bettenhausen

The Wind Rises is a film about appreciating what you have. In the film, the majority of characters are obsessed with advancements and change. They believe that change is the only way to be better. Opposingly, Jiro appreciates what’s in front of him and uses that as inspiration. He doesn’t always look for what is new and innovative to change things for the better. He likes to meet the world where it’s at. While out to eat with his friends he appreciates the shape of a fish bone. When visiting German aircrafts, he found the older simpler designs more fascinating, because they worked at their simpler state of being.

Jiro wants better just like his coworkers but doesn’t ask more of what is. The same goes for his love for Nahoko. He falls for her. When her needs change he meets her where she’s at and continues to love and support her. He loves her at her core. He loves planes at their core. He wants to help improve both in any possible way but accepts the limits the world has given him in doing so. In the end he’s alone. He advanced his planes and both the planes and Nahoko advanced to another world. He’s left with the memories of what he accepted and loved and now has time to think about what more he can do in this current world.

This concept can easily be transferred to the ideas of nature and how we treat it. When you love and appreciate nature as it is, you get more from it. You can find not only joy but also support and inspiration. If you disregard it, you will be left alone with nothing but memories.

Princess Mononoke

by Heidi Cha

Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke explores the precarious balance between humans and nature, particularly in the aftermath when this balance is disrupted. The film also highlights how humans rely on nature to survive, yet often fail to show respect for the forest as they exploit its resources and push forward with industry. Nature in Princess Mononoke isn’t just scenery but also alive; it is alive in a way that is sacred and home for the spirit gods and animal guardians who live and defend the forest. This plot reminds us that our environment isn’t just a resource but a living system we are part of. By visualizing the beauty and ferocity of nature, Miyazaki encourages us to rethink each of our personal relationships with nature. The movie’s message is that coexistence is the correct way, not domination. Princess Mononoke influences us to truly value what it means to conserve our nature, whether it’s protecting the land, reducing waste, or appreciating the natural beauty around us. The movie well connects nature to human emotion, helping us to live in a more sustainable way and in harmony with the earth.

The Boy and the Heron – Parakeets, Pyrokinetics, and Human Progress

by Terena Chen

The Boy and the Heron, while not having an overt environmental message, has it haunting the context and worlds of the story. The film uses its visual medium to juxtapose humanity’s continued march and the world it tramples upon for its gains. The warawara represent the innocent seeds of life. They’re depicted as harmless, defenseless even. On the other hand, the parakeets symbolize civilization, where individuals have devolved into flamboyant, loud creatures that prioritize their need to consume and maintain their society regardless of the needs of other beings. The parakeets are a warning for humanity’s self-obsession, where we are likely to doom ourselves if we act without thinking critically. Another kind of bird, the pelicans, represent nature in this narrative. Pelicans are wild birds who, unlike the parakeets, have no inventions or society, and are focused on survival. They feed on the warawara out of necessity, as the world lacks food for their young. This contrasts heavily with the ever-feasting parakeets, who have troves of food and enormous kitchens to serve their kind, along with being well-known to feed on humans; by consuming and controlling food in this world, they leave other denizens of the world struggling for survival.

Ponyo

by Chen Chiligiris

Hayao Miyazaki’s Ponyo analyzes the relationship between man and nature through its own childlike wonder and fantastical interpretation of the world; the sea is depicted as both harmonious and chaotic, highlighting the volatile complexion of the natural world around us. The deep, lush blues embedded into the film’s color palette and identity as well as the beautifully animated ocean waves showcases just how beautiful the sea is as an undisturbed natural force. It is teeming with life and color, and the simple act of watching the sea invokes a sense of serenity that is both true to life yet unique to the experience of the film at the same time. To contrast that, however, the sea (and nature as a whole) can be horrifying, destructive and violent. Tsunamis and floods can destroy homes and separate families. Natural disasters cannot be controlled or reasoned with. However, the disruption of nature only brings about greater suffering. Nature may be unreasonable, but coexistence is also necessary for us; Ponyo argues that taming nature is needless and may lead to more destruction if left unchecked, yet, at the same time, we should live alongside nature and make the best of our own coexistence with it. In both Miyazaki’s film and our real lives, the sea is a living, breathing force, but that does not mean it needs to be tamed.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya

by Vasunandan Dar

In The Tale of Princess Kaguya, director Isao Takahata explores the importance of maintaining a close relationship with nature through the life of Kaguya, a princess raised by bamboo cutters. Kaguya’s happiest memories were during her childhood when she lived in the wilderness, surrounded by forests and mountains. As Kaguya grows older, she moves to a mansion in the capital city.

The capital is distant from the wilderness that Kaguya grew up in, indicated by the contrast between the vibrant, colorful visuals of the forests and the muted color palette of the capital. This contrast mirrors Kaguya’s current state: she is confined to her mansion and feels disconnected from nature, desperately wanting to return to her old home. Through Kaguya’s predicament, Takahata shows the viewers that they should strive to embrace nature in their lives, as separating oneself from the natural world leads to sorrow. A pivotal moment in the movie is when Kaguya finally takes a trip outside her mansion to view the cherry blossoms. Under the blossoms, Kaguya’s childhood happiness returns, only to leave with the realization that she has to return to the mansion, isolated from nature again. The beauty of cherry blossoms is fleeting, as they bloom for a short time. Through these trees, Takahata depicts nature as transient and fragile, underscoring the need to preserve it. Today, when society is desensitized to the rampant destruction of the natural world, Kaguya’s story frames ecological conservation as something more personal and essential for our happiness.

The Secret Life of Arrietty

by Jasmine Gomez

The Secret Life of Arrietty is a film enveloped in nature. As in many Ghibli movies, it is not only the art that exhibits the beauty of nature, it is also the story and the characters that shine through to show the importance of the environment.

There is a lot of conversation throughout the film discussing the disappearance and the dying out of Arrietty’s people, known as “The Borrowers”. When they are discovered by humans, they either are forced to leave their homes, or they disappear, never to be heard from again. Humans pose a formidable threat as they are constantly changing the world they live in and the ones that have to pay the price are the borrowers and the creatures living in the environment around them.

This brings light to issues that happen in the real world. There are many animals that are endangered and that go extinct because of the actions of humans. The discussion of environmental changes in the film can bring conversation to ecological conservation, and demonstrates the importance of awareness and empathy for the environment and its creatures. Movies such as The Secret Life of Arrietty and other Ghibli films can exhibit important ecological messages of preservation and can inspire people to protect the environment.

Pom Poko

by Sophia Kim

The way that nature is depicted in this film is important to the film’s environmental themes and even more so the way humans and nature interact. This relationship in the film is very nuanced. Although initially it seems obvious that it presents the dynamic that humans are “bad” and destroy nature, a scene at the end of the movie presented another human to nature interaction. The tanuki make one last effort to remind the humans of what life was like before industrialization. This momentary scene didn’t just show untouched forests but a natural life where humans and nature coexisted. Farms and shrines replaced the high rise apartment buildings and it showed a much simpler time before the industrial development. This allowed me to consider that humans and nature can coexist peacefully with the proper respect for each other. The tanuki in Pom Poko are humanized with personalities and their clothing in their character designs. The interactions between the tanuki are reflective of human relationships and this fosters empathy among the viewers. For many viewers that haven’t previously considered their role in the environment it leaves you with deeper considerations of how humans interact with the environment and the importance of ecological conservation. This ties in with the importance of connecting film storytelling and ecology. Sometimes through viewing stories and following characters we can empathize more than just viewing a news story or a documentary. We care for the characters and their challenges and root for them.

The Cat Returns

by Dung Le

The movie I was given was The Cat Returns, which features a young girl named Haru who gets taken to a kingdom of cats after coincidentally saving the kingdom’s prince, Lune. While this movie doesn’t emphasize nature as strongly as other Studio Ghibli films, the biggest nature element of this movie would be the animals, or cats. At the start, Haru’s ability to communicate with cats is a small example of how she is connected with nature in her own way. And when she saves Lune, she is rewarded which to me is a message that we should be more kind and aware towards animals living alongside us. Additionally, in this cat kingdom, the cats behave very similarly to humans. They wear clothes, throw parties, etc. I feel that this aspect of the cat kingdom showed how when something part of the natural world, such as animals, start to become too immersed with the human world, it can become unnatural and strange in a way. To conclude my thoughts, this movie specifically encourages viewers to care about animals and how they are intertwined with our human world. Storytelling like this reminds us that empathy toward nature often begins through small acts of respect and simply being aware.

Howl’s Moving Castle

by Yiwei Li

Ghibli films, such as Howl’s Moving Castle, influence our perception of nature by imbuing it with a sense of wonder, personality, and intrinsic value. This means that, to a certain extent, directors, including the director of this film, Hayao Miyazaki, humanize nature and imbue plants with life. Howl’s vibrant, magical meadows and majestic, breathtaking landscapes evoke deep emotional resonance in viewers. By contrasting this idyllic beauty with the desolation of a war-torn land, the film makes ecological destruction a personal and spiritual loss, rather than simply a distant political slogan. This powerful and emotive framework encourages us to view the natural world around us with a renewed sense of empathy and gratitude. The need to protect the environment is a widely acknowledged topic; many people have seen slogans and phrases since elementary school, but how many actually take action? However, after watching movies like Howl’s Moving Castle, many people are likely deeply impressed by the sky, overwhelmed by dark clouds and pollution. This sows a seed in the audience, making them more concerned about environmental issues.

Kiki’s Delivery Service: Sometimes We Just Need a Break

by Sophia Liu

Kiki’s Delivery Service highlights the contrast between nature and modern civilization. In the film, Kiki has just settled into a bustling city to begin her journey as a witch-in-training. While her delivery service is successful, the demands of city life and disconnect from other residents tires Kiki. Eventually, she experiences burnout, losing her motivation and self-identity.

When all seems lost, visiting her artist friend Ursula draws Kiki out of her slump. The two spend time at Ursula’s cabin in the woods, surrounded by creative inspiration. Ursula’s peaceful cabin contrasts the endless hum of city life, showing Kiki a different kind of fulfillment. Nature is represented as a calming force that allows her to take a breath of fresh air and remember her purpose. This scene emphasizes how humans can coexist with nature, drawing strength and inspiration from its beauty.

Kiki’s Delivery Service encourages us to notice the natural world in our everyday lives, whether it’s the rustling of wind or the ripples of waves. We are reminded to appreciate our relationship with nature, as it helps us find inner peace. Therefore, connecting a film with ecology fosters a connection to the natural world that can lead to a sustainable future.

Spirited Away

by Patricia Miszczak

One of the most notable themes throughout Spirited Away is greed and how it manifests in various individuals under differing circumstances; this is a unifying trait seen in both the humans and spirits drawing a connection between the inherently different creatures. For example, the gluttony of Chihiro’s parents transforming them into pigs as well as the superficial monetary desires of the bathhouse owner Yubaba. A major consequence of humanity’s greed that is highlighted in the movie is the exploitation and destruction of natural resources and the environment as a whole. However, the film also depicts how humans have the capability of restoring environmental balance through respect, moderation, and consideration for nature. This is demonstrated by Chihiro’s ability to cleanse the heavily polluted River Spirit by physically removing the copious amount of waste that is characteristically human, such as tires and bicycles. Nature is depicted as a sacred and mystical entity that is corrupted by human greed but also shows gratitude when cleansed and restored by humans. Furthermore, Haku himself is a manifestation of the Kohaku River that was destroyed by housing development; the fact that Haku is as a fellow child that forms a deep friendship with Chihiro appeals to the audience’s emotions making them reflect on the disheartening effects continuous modernization and industrialization have on the planet. As a result, these parallels between the fantastical spirit realm and reality may influence audiences to feel more admiration towards the natural world and to seek a return to nature, similar to Chihiro’s promise to reunite with Haku.

Porco Rosso

by Humza Qazi

Unlike Princess Mononoke or Pom Poko, the high-flying yet melancholic Porco Rosso — both the film and its titular porcine protagonist — is not primarily concerned with themes of environmentalism. However, while subtle in execution, there are still glimpses of such themes throughout the film, which directly tie to Porco’s growth as a character. Take, for example, Porco’s hideout: a secluded limestone cove on an island in the Adriatic Sea, complete with a sandy white beach and a glittering, cerulean shoal. While undoubtedly beautiful, Porco’s hideout is representative of the pilot’s strict adherence to social isolation; Porco only ever goes into town when in need of supplies for his plane, having otherwise forgone his humanity. This changes, however, when he brings Fio — his new mechanic and co-pilot, with the latter being much to his initial dismay — back to his hideout later in the film. Where Porco has always elected to remain on the beach, Fio enthusiastically charges into the shallow water, symbolizing the way(s) in which she has broadened Porco’s perception of his own blossoming humanity. Ultimately, nature is perhaps at its most beautiful when shared with the people that we care about; after all, where the cove remains unchanged in its serenity, it is notably the self-loathing Porco Rosso that is softening toward sharing his home with Fio.

Grave of the Fireflies: Fireflies from the Bombers

by Shang Sai

Hideto Hoshina pointed out in his study on fireflies in modern culture that the connection between fireflies and souls have become a traditional image in Japanese literature since the Heian period.1 Grave of the Fireflies is a continuation of this tradition—using fireflies as a requiem.

However, another interesting metaphor lies in the title. Nosaka Akiyuki named the original work as 火垂るの墓 (Hotaru no haka), and “火垂” (hotaru) here is the ancient name for fireflies in Japanese. It could be, very ironically, directly translated into “the falling fire” or “the hanging fire”. In this specific work, obviously, it could also be referring to the firebombs dropped by the American bombers.

Unlike in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, nature and the environment aren’t a primary concern in Grave of the Fireflies. Rather, it’s hard to imagine somebody worry about the greenhouse gas emissions from the tanks or the survival of wild animals in zoos during wartime.

Let’s fight—fight for a world that such we are still able to have those concerns.

The black spots are traces of insects—probably including fireflies—that failed to escape from the train.

1 Izumi Shibuki’s tanka: 物おもへば沢の蛍も我が身よりあくがれ出づる魂かとぞみる

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

by Anh Do Tuong

Set in a post-apocalyptic world devastated by violence and industrial civilization, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind presents one of Studio Ghibli’s clearest and most powerful environmental messages. The film draws direct parallels to humanity’s relationship with nature through two interconnected themes: pacifism and coexistence. By showing the destructiveness of blind rage, the story shows us that retribution only deepens suffering, while empathy and understanding lead to true progress. Nausicaä’s environmental vision extends this by portraying nature as a living system with agency and self-correcting tendencies.

The Sea of Decay, feared by most characters, is revealed to be purifying the polluted earth and producing clean water, showing that what humanity perceives as a threat may, in reality, be its livelihood. However, not all recognize this balance. While Nausicaä’s people coexist peacefully with nature, the Tolmekians and Pejite see it as an enemy – both tribes attempt to burn it down to “restore” civilization, even going so far as to use nature as an agent of destruction so that they can then destroy nature themselves. Though fictional, the world of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind reflects on our own relationship with nature, sending a powerful message: humanity’s survival depends not on mastery over nature, but on balance, understanding, and coexistence with it.

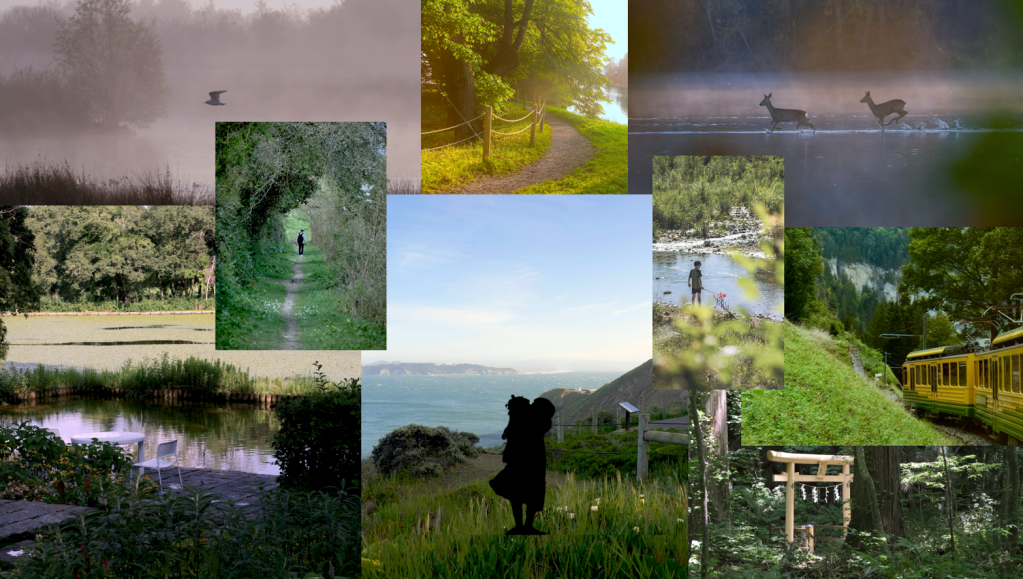

When Marnie Was There

by Tori Mays

In the film When Marnie Was There, Anna, the main protagonist, retreats to the marshland countryside to escape her stressful, isolated life in the city of Tokyo. The tranquil setting allows her space to breathe, reflect, and heal. This reflects how people in real life seek solace in nature for peace and clarity. Whether walking, sitting by a lake, or simply being outdoors, natural spaces help us reset our minds and emotions. Studio Ghibli’s portrayal of the marsh and the countryside suggests nature is not separate from us. We rely on it to recover from daily pressures and anxieties. Anna’s bond with the landscape reminds viewers that being in nature isn’t about activity; sometimes, it’s simply about presence. The film emphasizes that the natural world offers comfort and balance that cities and technology cannot, underscoring the importance of protecting and preserving these quiet spaces.

Castle in the Sky

by Izzy O’Day

In Castle in the Sky, Studio Ghibli presents a deeply layered exploration of environmental themes. This is shown through the tension between human advancement and the natural world. The floating island of Laputa began as a symbol of human technology and innovation. It now stands as a warning, one of an abandoned utopia that has been overrun with lush vegetation and peaceful wildlife. The overgrowth of nature atop Laputa depicts how, even in the face of human ambition and war, the natural world can reclaim itself and persist. Miyazaki contrasts the pastoral beauty of rural life with the destructive industrialization of military and mining forces. It shows the destructive difference between those that can live in peace with the earth, and those who exploit nature and cause imbalance and violence. The film emphasizes the importance of humanity and caretaking. The robot guardians of Laputa take care of animals and gardens, despite being mechanical. This suggests a gentler form of coexistence. This portrayal brings viewers to reflect on the consequences of unchecked technological advancements and reminds us of the value of preserving ecological balance. Caste in the Sky urges a deeper respect for nature’s resilience and warns the dangers of ruining our relationship with the natural world. By weaving ecological caution into a fantastical narrative, the film reinforces how stories can shape our attitude toward conservation and encourage audiences, especially younger ones, to see the environment not as a resource to dominate, but as a partner to protect.

Whisper of the Heart

by Lily Windmiller

Although it may not be as on-the-nose about environmentalism as other Ghibli films such as Pom Poko and My Neighbor Totoro, Whisper of the Heart offers a more modern reflection on how humans interact with nature in an urban environment. The film demonstrates that even in a modern environment such as Tokyo, humans can still take time to notice and appreciate the living world around them. One key example of this is Shizuku’s deep respect for animals, seen when she follows a strange cat that gets off at the same train stop as her. Instead of ignoring the animal, Shizuku respects him and makes an active effort to talk to the cat as if he were a friend, showing her compassion for the animals that share her surroundings. Furthermore, we can see Shinzuku’s awareness of the tension between the modernization of her home and the destruction of nature used to create it in her parody of “Take Me Home, Country Roads”, entitled “Concrete Roads”. The lyrics, including lines such as “Concrete roads, everywhere I go…” and “Chopped down forests, buried our valleys, my hometown’s down concrete road…” show her recognition of the environmental impact of urbanization in her community. By weaving these subtle environmental messages into the story, Whisper of the Heart leaves viewers more conscious of nature amid city life.

Only Yesterday

by Hu Xinran

In Only Yesterday, Studio Ghibli beautifully contrasts urban and rural life through the eyes of Taeko, a Tokyo office worker who spends her vacation in Yamagata’s countryside. The film reveals two distinct worlds: the city, filled with cars, tall buildings, and emotional distance, and the countryside, where people live closely with the land. One unforgettable scene shows Taeko joining farmers to pick safflowers at dawn. As sunlight streams through the mountains, everyone pauses to pray toward the rising sun. It’s a moment that captures the film’s vision of harmony between humans and nature. Nature is not something to be conquered or romanticized, but it is a living partner that sustains life. The villagers nurture the soil, and in turn, nature feeds them. This interdependence reminds us that respect for the environment is essential for our own survival. In the film, Taeko has loved rural life since she was a little girl, but her passion has always been suppressed by her family. Her journey symbolizes a quiet rebellion against the alienation of modern city life. She returns to simplicity, authenticity, and the rhythms of the earth. Only Yesterday encourages viewers to reconsider their own relationship with nature and to see ecological care not as a duty, but as a form of gratitude.

Both neglecting and attempting to bend the natural world to human desire will lead to humanity’s destruction. Miyazaki’s work once again insists on the power of nature, suggesting humanity lives alongside it, and to not let humanity’s needs cloud our consideration of the world around us.

My Neighbor The Yamadas

by Ariana Zhang

In Isao Takahata’s 1999 film, My Neighbor The Yamadas, Takahata emphasizes nature as a subtle constant in the snippets of everyday family life presented in the movie. Whilst My Neighbor The Yamadas doesn’t tackle environmentalism as directly as other Studio Ghibli films, the largely minimalist watercolor animation style means that whenever natural elements are included, they stand out. Even beyond scenes with more obvious weather metaphors like in the opening marriage scene, many of the more grounded, mundane mini-stories still incorporate nature as an element. Whether it’s rain falling down and looking for an umbrella or it’s the sun shining with fluffy clouds in the sky, the general lack of other backgrounds and detail highlights the role of nature in shaping the occurrences of everyday domestic life and evoking emotion. Despite living in a suburban environment, the domestic happenings of the Yamada family still are connected with nature in most of their presented snippets, and through this, we’re reminded of how we can be more mindful of the presence of nature plays in our own lives.